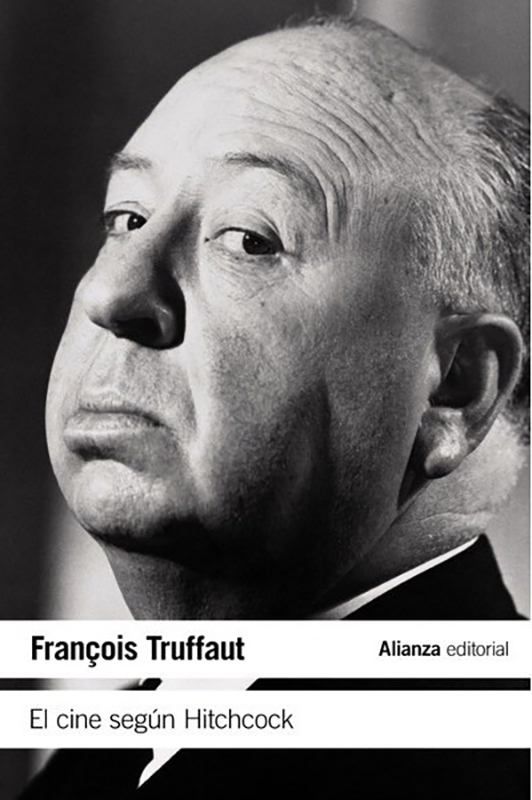

Si existe un libro que todos los cinéfilos deberían leer ese sería “El cine según Hitchcock” (1966), escrito por François Truffaut y que recoge las interesantes conversaciones que el director francés mantuvo con Alfred Hitchcock. En el 2015, Kent Jones realizó un estupendo documental sobre dicho encuentro en el que también opinaban otros grandes como Martin Scorsese. Hablamos de cine en mayúsculas, pero también de literatura, pues los dos cineastas tenían en común una cosa: buscaron la inspiración para muchos de sus films en novelas y, en ambos casos, no eran necesariamente éxitos de ventas. La idea era encontrar una buena historia, no hacer la versión cinematográfica de un best seller.

Hitchcock era sinónimo de perfección y siguiendo esa máxima de no dejar ningún detalle al azar, su primera obra maestra, “Rebeca” (1940), estaba basada en la novela homónima de Daphne Du Marnier. Jugaba sobre seguro, pues el año anterior, el director británico ya había recurrido a esta escritora para conferir de una cautivadora trama a “Jamaica Inn” (1939), que contaba entre su elenco con Charles Laughton y Maureen O’Hara.

Pero la mejor conjunción entre Hitchcock y Du Marnier la encontraríamos en “Los pájaros”, un relato que en 1963 nos conduciría a un pueblo donde el aleteo de unas alas de gaviota era sinónimo de muerte. La autora no siempre estuvo satisfecha con el tratamiento que el director hacía de su obra, algo que ha ocurrido a menudo en la historia del Séptimo Arte. De sobras es conocido que a Stephen King le disgustó la adaptación que Stanley Kubrick hizo de “El resplandor”. Personalmente si Kubrick se hubiera fijado en cualquier cosa que hubiese escrito le estaría eternamente agradecido y no sería tan quisquilloso.

Sin salir del género de la literatura fantástica, Hitch ya había dado en el clavo tras fijarse en una novela de Robert Bloch que, como muchos intelectuales durante los años cincuenta y sesenta, sobrevivía gracias a guiones para películas y series televisivas. Entre tanto encargo ajeno, Bloch tuvo tiempo de forjar una historia sobre un loco que vivía en un motel subyugado por su madre y sí, aquel tipo se llamaba Norman Bates y en la gran pantalla llevaría el rostro de Anthony Perkins. Pocos films resumen tan bien en su título una sensación tan asfixiante como “Psicosis” (1963).

En cambio, Truffautt se acercó a la ciencia ficción en “Fahrenheit 451” (1966), un ejemplo excesivamente actual de un mundo dominado por las pantallas televisivas —hoy en día serían los teléfonos móviles— y donde los libros estaban fuera de la ley. Por cierto, el título hace referencia a la temperatura a la que arde el papel. La mente que se encontraba tras esta inquietante distopía era la de Ray Bradbury, una verdadera referencia dentro de la ciencia ficción que en 1950 llenaría de lirismo sus “Crónicas marcianas”.

Lo más curioso de todo es que dos genios tan distintos entre sí coincidieran en un escritor, Cornell Woolrich, que firmaba sus novelas bajo el pseudónimo de William Irish y que fue quien permitió a James Stewart mirar a través de “La ventana indiscreta” (1954). Aunque sería el galo el que recurriría en más ocasiones a Woolrich y lo haría con dos films francamente extraordinarios, “La sirena del Mississippi” (1969) y “La novia vestía de negro” (1967).

Este último relata la historia de una mujer que venga la muerte de su futuro marido, asesinado por un grupo de insensatos justo el día en que se celebraba la boda. Interpretada por Jeanne Moreau, la caza del hombre es tan fría como implacable. Si eso no os recuerda a los dos volúmenes de “Kill Bill” de Quentin Tarantino dejaría de leer en este preciso momento.

ENGLISH:

The authors who inspired Hitchcock, Truffaut… and Quentin Tarantino?

If there was one book that all film buffs should read, it would be François Truffaut’s The Cinema According to Hitchcock (1966), a collection of a number of interesting conversations that the French director had with Alfred Hitchcock. In 2015, Kent Jones made a brilliant documentary about this meeting, in which other greats like Martin Scorsese also weighed in. This is cinema with a capital C, but it’s also great literature, since the two filmmakers had one thing in common: they sought inspiration for most of their films in novels. However, they weren’t exactly looking for bestsellers: the idea was to find a great story, not to make the movie version of a best seller.

Hitchcock has always been synonymous with perfection, and following that maxim of leaving no detail to chance, his first masterpiece, «Rebecca» (1940), was based on the novel of the same name by Daphne Du Marnier. He was playing it safe, since the year before, the British director had already turned to this writer to spin a captivating tale for “Jamaica Inn” (1939), which featured Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara in its billing.

However, when we see Hitchcock and Du Marnier really seeing eye to eye is in “The Birds”, a story that in 1963 would lead us to a town where the flapping of a seagull’s wings was synonymous with death. That said, the author was not always satisfied with the director’s approach to his work, something all too common throughout the history of The Seventh Art. It is well known that Stephen King disliked Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of “The Shining”. Personally, if Kubrick had noticed anything I had ever written, I for one would be much less picky and eternally grateful.

Without leaving behind the genre known as fantasy literature, Hitch had already hit it big after setting his sights on a novel written by Robert Bloch, who, like many intellectuals during the 1950s and 1960s, was able to scrape by thanks to movie and television series scripts. In between assignments, Bloch found the time to forge a story about a madman who lived in a motel and was overpowered by his mother. Yes, that madman’s name was Norman Bates, and yes, Anthony Perkins would bring him to life on the big screen. Few films are able to summarize a greater asphyxiating sensation in their title as “Psycho” (1963) did.

In the meantime, Truffautt was flirting with science fiction, bringing us “Fahrenheit 451” (1966), an excessively modern example of a world dominated by television screens – today they would be mobile phones – in which books were outside the law. (By the way, the title refers to the temperature at which paper burns.) Ray Bradbury was the mastermind behind this disturbing dystopia, an absolute reference within science fiction, and a man who in 1950 would fill his “Martian Chronicles” with lyricism.

Even more interesting is the fact that these two geniuses, who were so different from each other, had such similar views about one writer, Cornell Woolrich, who went by the pen name of William Irish, and who was reponsible for letting James Stewart look through the “Rear Window” (1954). The Frenchman would be the one to resort to Woolrich more often, including two downright extraordinary films, “The Mississippi Mermaid” (1969) and “The Bride Wore Black” (1967).

The latter tells the story of a woman who avenges the death of her future husband, murdered by a group of halfwits on the day of their wedding. Played by Jeanne Moreau, the manhunt is as cold as it is relentless. And if that doesn’t remind you of Quentin Tarantino’s two “Kill Bill” flicks, you’d might as well stop reading at this very moment.

Translation by Jessica Jacobsen