Extracto del librisco Cien años en la Carretera.

English text below by Jessica Jacobsen.

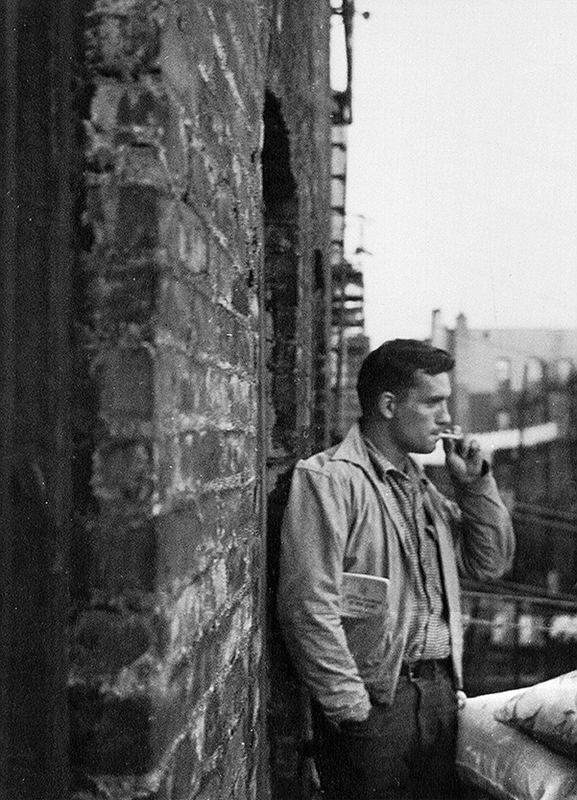

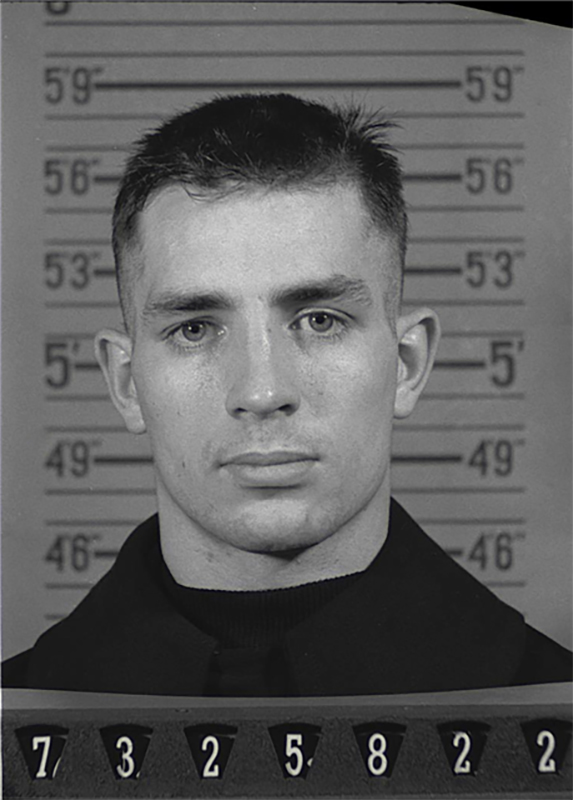

Llega a las librerías esta semana Cien Años en la Carretera, libro y disco que celebran la vida y obra de Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), editado por Allanamiento de Mirada. Dirty Rock adelanta en exclusiva un fragmento dedicado a los vínculos que unen las obras de Bob Dylan y Kerouac, en el centenario del escritor esencial de la Generación Beat.

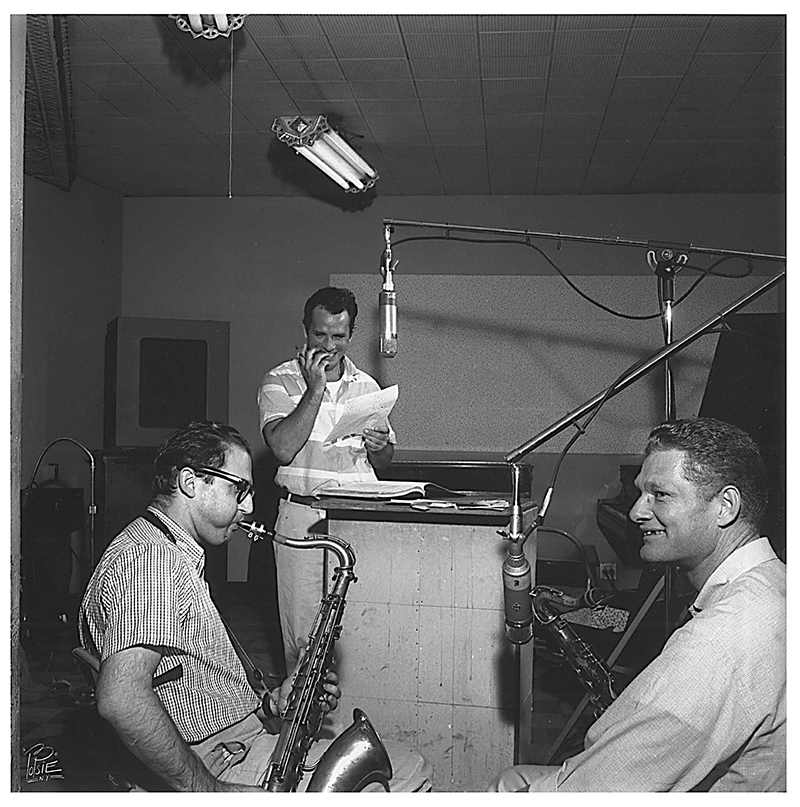

El “librisco” reúne talentos de varias disciplinas congregados por una pasión compartida hacia el autor de On the Road (En la Carretera). La biografía musical la firma Miguel López, colaborador de Dirty Rock, y ahonda en la huella que dejó el jazz en los libros de autores de la Generación Beat. También se refleja en la obra el impacto del novelista sobre algunos de los músicos más relevantes de nuestro tiempo: Tom Waits, Patti Smith, Van Morrison, David Bowie o Grateful Dead, entre otros. Varios artículos de poetas, cineastas, periodistas o filólogos exploran también el legado del escritor desde distintos ángulos con alta carga emocional y poética.

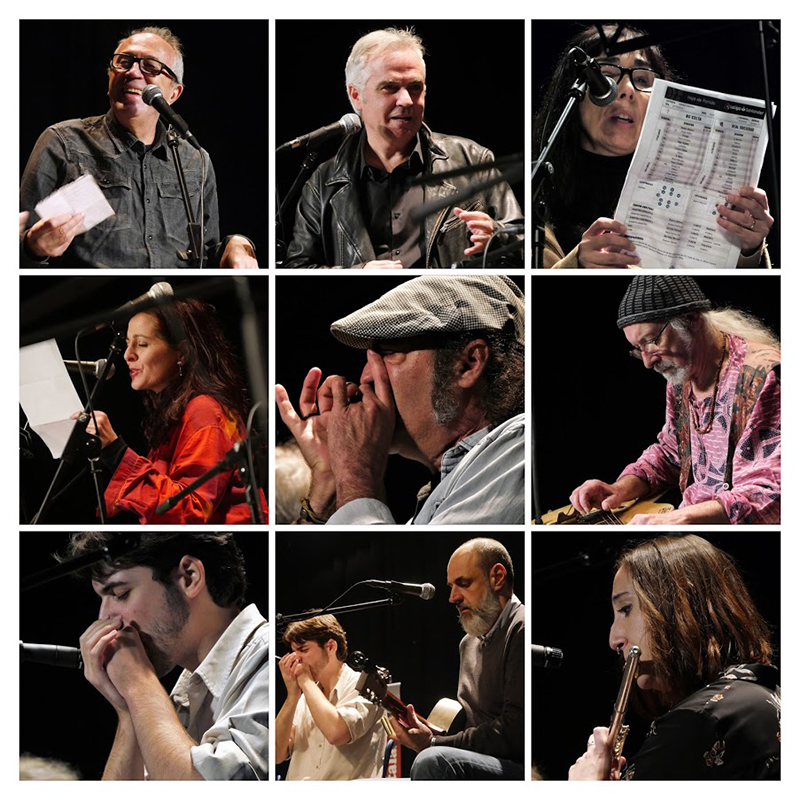

Flaco Barral es el motor musical que ha conducido el proyecto sonoro y ha reunido a artistas de primera fila para ofrecer una traducción sonora de En la Carretera. El paisaje del disco es cambiante a lo largo de la escucha e irradia una luz poderosa para seguir el camino de la salvación por carreteras llenas de polvo y oscuridad.

Cantantes, compositores o instrumentistas han devuelto durante décadas a Kerouac el amor que el escritor demostró por la música. El cordón umbilical que conduce desde el novelista hasta tantos artistas no se debe solo a la pasión compartida por las melodías. Ese lazo parte del arrobo ante los libros publicados por el autor más famoso de la Generación Beat y también por las vivencias comunes que atan a los profesionales a la carretera. El trasiego continuo en las giras, de ciudad en ciudad, de hotel en hotel, conecta sus espíritus. Casi todos los músicos que admiran a Kerouac han probado además otro tipo de viajes interiores, experimentando con drogas para llegar más lejos en sus formas de expresión artística, profundizar en su deseo de espiritualidad o, simplemente, para divertirse.

Abundan los músicos que han reflejado en sus composiciones el influjo de Jack Kerouac y otras luminarias de la Generación Beat, a veces de forma directa, a veces con alusiones menos descaradas. Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Tom Waits, Grateful Dead, Patti Smith, The Doors, Van Morrison o David Bowie, entre otros muchos, incorporaron a las letras de sus canciones el mensaje que proclamaban los escritores beat. El reconocimiento a ese grupo literario no ha decaído con el paso del tiempo. Los talentos musicales emergentes recogen la antorcha de los clásicos y muestran sin tapujos su deuda con el autor de On the Road. Así ha pasado con Eddie Vedder (Pearl Jam), Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth), Joe Strummer (Clash) o Michael Stipe (REM), entre otros, pero la lista podría ocupar varias páginas de este libro.

Bob Dylan nunca se ha alejado mucho de la prosa espontánea que aprendió de Kerouac. Inventa una poesía sonora sin precedentes, en parte como herencia de los escritores de la Generación Beat, en parte por el océano de influencias musicales que acumula desde que le salieron los dientes. Woody Guthrie introduce el tren en su cosmogonía, mientras Jack Kerouac pone en su cabeza la carretera y un modo de escribir. Las composiciones concentradas entre 1963 y 1966 recogen dosis elevadas del espíritu beat, aunque la proyección de esos libros se extiende a toda su trayectoria y llega hasta su último disco, Rough And Rowdy Days (2020). Confiesa en la canción Key West (Philosopher Pirate): “Nací en el lado equivocado de las vías del tren, como Ginsberg, Corso y Kerouac, como Louis, Jimmy, Buddy y los demás. Bueno, quizá no sea lo que hay que hacer, pero sigo contigo de principio a fin. Ahí en las tierras planas, muy abajo en Key West”.

Abundan en los discos iniciales de Dylan canciones transmutadas en poemas surrealistas, fruto de la escritura automática, acelerada por las anfetaminas y salpicada de automóviles y ferrocarriles.

Buena parte de la riqueza literaria de esas canciones inmortales procede de los libros de la Generación Beat. Al de Minnesota le parecían muy pobres las letras de la banda sonora dominante en sus años mozos, ajenas a su tiempo y a la realidad juvenil que peleaba por salir a flote. Tira una piedra sobre esas aguas estancadas y encuentra en la obra de Kerouac un remolino de emociones que sirve como catalizador de cambios: “Seguía encendiendo la radio, probablemente más por un hábito sin sentido que por cualquier otra cosa. Lamentablemente, todo lo que se tocaba no reflejaba más que leche y azúcar, y no los temas reales de Jekyll y Hyde de la época. Las ideas de En la Carretera, Aullido y Gasolina que indicaban un nuevo tipo de existencia humana no estaban allí, pero ¿cómo podrías haber esperado que así fuera? Los singles de 45 eran incapaces de ello“, explica el rapsoda en su autobiografía Chronicles Vol. 1.

Ese universo oculto le interesa y se arrima al hábitat alternativo. “Mineápolis fue la primera gran ciudad en que viví. Llegué del desierto y topé con la escena beat, los bohemios, los bebop, todo estaba muy conectado. Saint Louis, Kansas City, ibas de una ciudad a otra y encontrabas el mismo panorama en todos esos lugares, gente que iba y venía, nadie con sitio fijo”. Y añade Dylan: “Había muchos poetas y pintores, becarios, vagabundos, expertos en una cosa u otra, que habían dejado la vida típica de ´nueve a cinco´. Siempre había muchas lecturas de poesía, T.S. Elliot, E.E. Cumings. Fue algo de eso lo que me despertó, Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso y Ferlinghetti, eso tenía sentido para mí”.

También cuenta que “Ginsberg y Jack Kerouac me inspiraron al principio”. “Por lo que recuerdo, leí On the Road quizá en 1959. Por supuesto, cambió mi vida como a cualquier otro”, recuerda. Y añade en sus memorias: “Ese libro había sido como una biblia para mí”. Otras publicaciones también habían encandilado a Robert Allan Zimmerman, como el poema Mexico City Blues, también de Kerouac. El bardo sentía una cercanía muy especial con esa escritura que prometía formas de expresión novedosas para entender el mundo, más en contacto con lo auténtico y no confinadas en cercados academicistas.

Cuando Bob Dylan llega a Nueva York frecuenta los cafés y locales propios de la bohemia, al igual que los miembros de la Generación Beat. En el Village, el recién llegado pasa algunas semanas con Jacques Levy, un amigo de Kerouac y letrista de The Byrds. El joven músico y Kerouac desembarcan en la Gran Manzana de manera similar a Paco Martínez Soria cuando llega a la capital: paletos inquietos que de pronto habitan en el centro del universo. Uno procede de Hibbing (Minnesota) y el otro de Lowell (Massachusetts), uno veinte años antes que el otro. Se diluyen en Nueva York y se enganchan creativamente a la ciudad más vibrante del país. Ambos son a su pesar la voz de su generación. Escriben o cantan sobre el paisaje humano más oprimido, aman a los vagabundos, rechazan el materialismo y buscan la pureza de la vida.

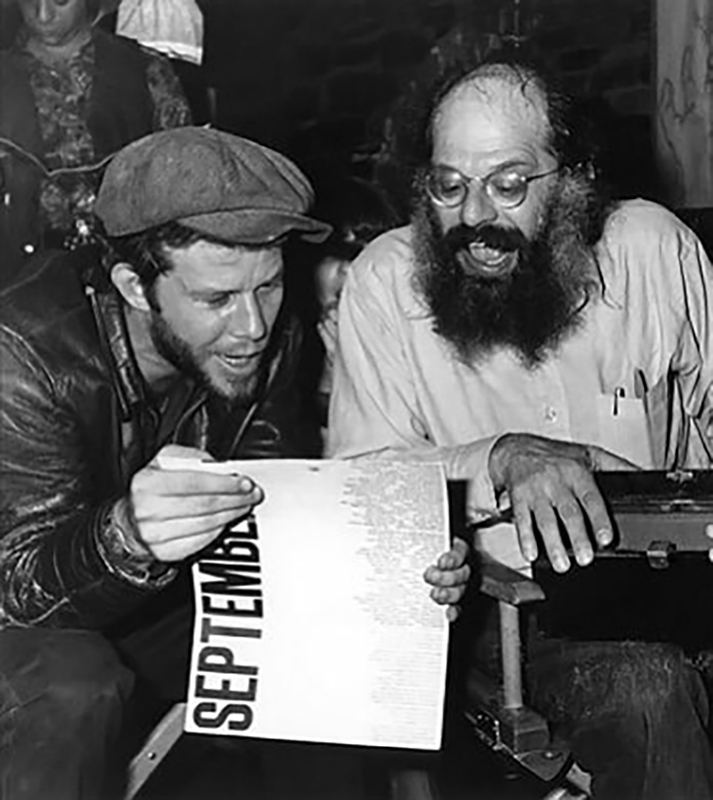

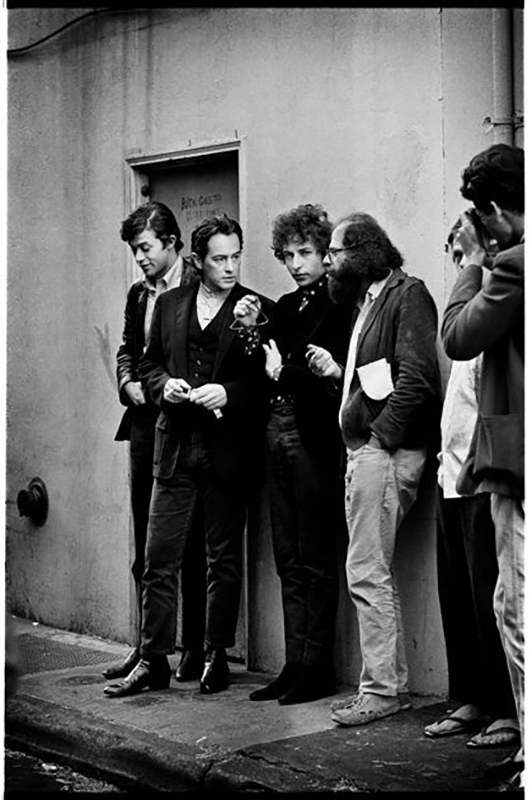

Al igual que Kerouac se encuentra con el autor de Howl en la ciudad de los rascacielos, Dylan también se topa con ese mismo poeta un par de décadas más tarde. Ese encuentro de Allen Ginsberg con el muchacho de Minnesota es un momento crucial para comprender el fuego creativo de los años sesenta. Ambos comparten muchas horas de vuelo y se contagian mutuamente sus delirios. El poeta y amigo de Kerouac amplía muy pronto su círculo de colegas dedicados a la música y se codea con el Olimpo del rock. Vive en primera línea momentos estelares como la grabación de We Love You (The Rolling Stones, 1967) o Give Peace a Chance (Beatles, 1969), además de apoyar a Lennon en su batalla para no ser expulsado de Estados Unidos en los años setenta. Hablando de los Beatles, los de Liverpool seleccionan a William S. Burroughs entre los personajes que aparecen en la portada de Sgt. Pepper´s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Dylan y el autor de El Almuerzo Desnudo comparten protagonismo en esa histórica foto desde entonces y para siempre.

El nexo de la Generación Beat y Dylan abarca desde las primeras lecturas de On the Road hasta la posterior complicidad combativa junto a Ginsberg o Ferlinghetti. El bardo de Minnesota visita junto al autor de Howl la tumba de Kerouac durante la gira Rolling Thunder Review, en noviembre de 1975. Ginsberg abre el libro de poesía Mexico City Blues y leen varios fragmentos. Hay solemnidad en esa muestra de veneración. Dylan apunta que desearía ser enterrado en un sepulcro sin nombre.

Ginsberg, Kerouac y Cassady se hicieron inseparables en los primeros momentos tras el encuentro. El poeta que luego pasó tanto tiempo con Dylan dijo en 1992 que su propia forma de escribir había estado modelada por Kerouac en la plasmación directa de los pensamientos y sonidos sobre la página de papel. El novelista aconsejó a Ginsberg que no revisara el primer texto de Howl ni lo retocara cuando se lo envió para conocer su opinión. Curiosamente, la histórica frase “First thought, best thought” (“la primera idea es la que vale”) es de Ginsberg tras el consejo de Jack.

El escritor Greil Marcus apunta en su Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads que canciones como Visions of Johanna o Desolation Road pueden enmarcarse en el estilo narrativo de Kerouac. Otro crítico relevante, Clinton Heylin, considera que la estructura de muchos versos de Freewheelin proceden más de Kerouac o Ginsberg que de Guthrie o Robert Johnson.

Pero es mucho mayor el peso que alcanza como influencia Allen Ginsberg. El autor de Howl se queda de piedra cuando escucha por primera vez A Hard Rain´s a-Gonna Fall, en 1963. “La iluminación ha pasado de una generación a otra. Es la primera revolución cultural que se produce sin derramamiento de sangre”, juzga el poeta. Estrechan lazos de inmediato y el inquieto barbudo aparece en lo que puede considerarse el primer vídeo musical de la historia del rock, Subterranean Homesick Blues (1965), en la parte trasera del Hotel Savoy, en Londres. Marianne Faithfull dijo que cuando Dylan tira al suelo los carteles con versos de la canción, procedentes de un rollo de papel, está rindiendo homenaje a On the Road. Chi lo sá.

En la secuencia de acontecimientos en la época, cabe recordar que Dylan escribe las canciones de Highway 61 Revisited (1965) un mes y medio después de la publicación de Desolation Angels. El título Desolation Row procede de ahí y proyecta su atmósfera por todo el disco. Dylan habla de los cambios de nombres (“And give them all another name”), justo la costumbre del baile de denominaciones que aplica Kerouac en sus novelas. Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues (1965) repite de alguna forma la narración del viaje por carretera en México que aparece en On the Road. También Visions of Johanna podría proceder de Visiones de Gerard, novela publicada en 1963.

Se ha escrito y hablado muchísimo sobre el accidente de moto de Dylan, en Woodstock, en 1966. Coinciden los dylanófilos en que el trovador no volvió a ser el mismo; sin embargo, escasean los que insisten en que previamente todo había cambiado en él tras la lectura de On the Road, un momento en que los hobos ya estaban en peligro de extinción y el músico se aferra al mito. Por eso declara al llegar a Nueva York que ha llegado hasta allí en un tren de carga, si bien lo desmentirá en sus memorias muchos años más tarde, cuando confiesa que recaló en la Gran Manzana en automóvil, otro símbolo de los beats.

Aunque Dylan se ha distanciado de esos inicios literarios, varios signos muestran que pervive ese fuego inicial que encendió Kerouac. Una prueba es el primer libro de Dylan, Tarantula (de 1971, aunque iba a publicarse en 1966). Ahí se percibe el influjo de estos literatos. También comparten la sesión de despedida de The Band, en 1976, en The Last Waltz. Durante la inmortal velada, suben al mismo escenario de Frisco el de Minnesota y dos distinguidos poetas de la Generación Beat: McClure y Ferliguetti. ¿Más pruebas? La gira eterna que inició Dylan en junio de 1988, Never Ending Tour (La Gira interminable), reconoce desde el nombre que el compromiso del autor de Blonde on Blonde con la vida en la carretera no tiene fecha de caducidad.

Kerouac o Ginsberg nunca estuvieron entre las quinielas de candidatos al Premio Nobel de Literatura. Cuando Dylan consigue el galardón en 2016 muchos seguidores sienten que ese día se hace justicia también a los escritores de la Generación Beat. Algunos críticos piensan que Like a Rolling Stone no existiría sin Howl, de Ginsberg, en cuya gestación influyó a su vez Kerouac. Ese reconocimiento mundial se extiende, de alguna forma, a los artistas rupturistas que sufrieron durante los años cincuenta del siglo XX hasta abrirse paso en el elitista panorama literario estadounidense. La Academia sueca explicó que su decisión reconocía la creación de nuevas expresiones poéticas en la gran tradición de canciones americanas. “¿Nobel? ¿No es el hombre que inventó la dinamita? ¡Ja, ja, ja! Mis posibilidades de ganar eran tantas como ir a la Luna”, responde al conocer la noticia.

Dylan encomienda a Patti Smith que viaje a Suecia para recoger el Nobel. La encargada de tan alto honor había estado entre los personajes más innovadores en sus comienzos, pisando el territorio compartido del punk y el rock, y siempre con la poesía como brújula musical. Como escribe Ronna C. Johnson, “el arte de Smith conduce las transiciones culturales y literarias que van desde el Beat (arte de resistencia) hasta el pop (arte de la simulación) y hasta el punk (el arte del rechazo)”.

La poesía, el desprecio a las normas, un alto individualismo y la innovación artística como necesidad son otros puntos comunes de Smith y los beats. La artista llega con una mano delante y otra detrás a Nueva York, en 1967. En 1975, con Horses, Patti Smith emite una afirmación rotunda de sus principios poéticos. Une los versos con la música punk en otros discos: Seventh Heaven (1972), Easter (1978) o Babel (1978). Se introduce así en las vanguardias neoyorquinas y el punk se fortalece. No hay nostalgia por los escritores desaparecidos, sino reivindicación del pasado literario para fortalecer las emergentes formas de cultura alternativa.

Smith ha reconocido que “casi todos los amigos que me gustaban estaban chiflados por Kerouac. Creo que conocí a Kerouac a través de ellos y como de segunda mano”. Eran gentes como Sam Shepard o Fred “Sonic” Smith. Llega a sentir que la presencia del autor de Visiones de Cody “siempre está en la aire”. Además de la cercanía a Burroughs o Kerouac, Patti Smith también compartió recitales de lectura con Corso y cantó en su funeral, en 2001. Entonces declaró: “Afortunadamente, Gregory fue una mala influencia para mí”.

Excerpt from the Book/CD Combo ‘Cien años en la Carretera’

Musicians and writers pay tribute to Kerouac on the 100-year anniversary of his birth

Cien Años en la Carretera (One Hundred Years on the Road), a book + CD combo that celebrates the life and work of Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), is set to hit your local bookstores this week. Dirty Rock gives us a sneak peek into the deep-seated tie that binds the work of Bob Dylan and that of Kerouac, on the centenary of the Beat leader’s birth.

Published by Allanamiento de Mirada, this new release alludes to a sundry list of artists from all walks of life, brought together by their shared passion for On the Road and the author who penned it. Miguel López, author of Cien Años en la Carretera, delves into the legacy of jazz left behind by Beat Generation authors and their works. Kerouac’s impact on some of the most important musicians of our time is also covered in the musical biography (including Tom Waits, Patti Smith, Van Morrison, David Bowie or the Grateful Dead).

López, collaborator of Dirty Rock, has brought together countless emotional and poetically-charged articles by a myriad of poets, filmmakers, journalists and philologists, as they explore the writer’s legacy from different angles.

Flaco Barral, the musical mastermind behind the sonic component of the project, has assembled a group of star-studded artists to delight us with an auditory translation of On the Road. The album’s soundscape wavers capriciously throughout, yet never ceases to radiate its powerful light that leads us down the path of salvation through dark and dust-laden back roads.

For decades, singers, composers and instrumentalists have done their best to reciprocate Kerouac‘s deep-rooted love for music. However, it isn’t just a shared passion for melodies that has brought the novelist and so many artists together; the bonding umbilical cord stems from the most famous author of the Beat Generation’s books about being on the road. The nostalgia of the constant bustle of touring, from city to city and hotel to hotel, is responsible for working so many greats into a frenzy and uniting their spirits. Most musicians who admire Kerouac have also tried to follow in his example regarding other kinds of inner journeys, experimenting with drugs to try to further their forms of artistic expression or deepen their desire for spirituality… or simply for a bit of fun.

Scores of musicians reflect (some more conspicuously than the rest) on the influence of Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation figures. For years, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Tom Waits, Grateful Dead, Patti Smith, The Doors, Van Morrison and David Bowie, among many others, have been infusing their lyrics with the messages that Beat writers proclaimed, and the appreciation of this influential literary group has not dwindled with the passage of time. Many current and up-and-coming musical talents have decided to carry the torch; not at all hesitant about showing their gratitude towards the On the Road novelist. The long list of names (that could probably fill up several pages of this book) includes Eddie Vedder (Pearl Jam), Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth), Joe Strummer (Clash) and Michael Stipe (REM).

Bob Dylan has never strayed far from the unconstrained prose he learned from Kerouac. Dylan’s unprecedented sonic poetry is partly an inheritance passed-down from Beat Generation writers and partly due to the vast number of musical influences that he has amassed since he first cut his teeth. Woody Guthrie introduced the train in his cosmogony, and Jack Kerouac steeped his mind with back roads and a certain form of writing. The most ‘beat-esque’ work he composed can be traced back to between 1963 and 1966. Nevertheless, the books’ trademark features can be found throughout Dylan’s entire career, even up until his latest album, Rough And Rowdy Days (2020). In the song “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”, he confesses, “I was born on the wrong side of the railroad track, like Ginsberg, Corso and Kerouac, like Louis and Jimmy and Buddy and all the rest. Well, it might not be the thing to do but I’m sticking with you, through and through down in the flatlands, way down in Key West.”

Dylan‘s early albums are chock-full of songs that have been transfigured into surreal poems; a product of unshackled writing, revved up by amphetamines and bestrewn with automobiles and train tracks.

A great deal of the literary insight of these immortal songs is deeply rooted in Beat Generation literature. The Minnesota native believed that the second-rate lyrics of what was so prevalently played on the radio in his day and age were alien to what was going on, and not at all in tune with the youth’s views that were starting to sprout up at the time. The ripple effect that Dylan produced in those stagnant waters from his unsuspecting nosedive into Kerouac’s work, would soon plunge him into a whirlpool of emotions: “I kept turning on the radio, probably more out of mindless habit than anything else. Sadly, whatever it played, reflected nothing but milk and sugar and not the real Jekyll and Hyde themes of the times. The On the Road, Howl and Gasoline street ideologies that were signaling a new type of human existence weren’t there. But what could we expect? It was something that 45 singles were incapable of [producing],” explains the rhapsodist in his autobiography, Chronicles Vol. 1.

He was captivated by this previously obscure universe and soon made his way towards an alternative habitat. “Minneapolis was the first big city I lived in. I came out of the wilderness and just naturally fell in with the Beat scene, the bohemian, bebop crowd; it was all pretty much connected. Saint Louis, Kansas City, you could go from one city to another and you’d find the same scene in all those places; people who came and went, we were all drifters.” Dylan went on to say, “There were so many poets and painters, scholars, drifters, experts in something or another, who had left the typical ‘9 to 5’ life. There were always a lot of poetry readings: T.S. Elliot, E.E. Cummings… Some of it woke me up. It was Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso, Ferlinghetti… I got in at the tail end of that and it was magic.”

He also recalled that, “Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac inspired me at first. […] From what I can remember, I read On the Road […] in 1959. Of course, it changed my life like no other.” He later added in his memoirs, “That book was like my bible.” Robert Allan Zimmerman had also been bowled over by some of the material, including Kerouac’s poem, “Mexico City Blues”. In fact, the poet, himself, felt especially attached to that piece; it promised new ways to express the intricacies of the world that were more in contact with what was real and not barred by academic fences.

When Bob Dylan found himself in New York, he started hanging around bohemian cafés and some of the places that the members of the Beat Generation were known to frequent. In the Village, the newcomer spent a few weeks with Jacques Levy, a friend of Kerouac’s and a lyricist who collaborated with The Byrds. […] Although Kerouac had done so some twenty years before the young musician, both men wound up in the Big Apple similarly: two restless country boys (one hailing from Hibbing, Minnesota and the other from Lowell, Massachusetts) who end up in the center of the universe. They fade into the New York backdrop and get creatively hooked on the most vibrant city in the country. With their prose and lyrics about the oppressed human landscape, Kerouac and Dylan unwillingly become the voice of their generations, upholding the vagabonds, rejecting materialism and seeking purity in life.

Following Kerouac’s footsteps once again, Dylan came face to face with Allen Ginsberg, poet and friend at the time of Kerouac’s. The pivotal meetup in that skyscraper-laden city was crucial for Minnesotan to fully understand the creative fire of the sixties. The two men fly high together, each feeding off the other’s individual delusions. The author of “Howl” soon began to widen his circle to more musically-charged colleagues, rubbing shoulders with the veritable Olympus of Rock. He experiences, first hand, extraordinary moments such as the recording of “We Love You” (The Rolling Stones, 1967) and “Give Peace a Chance” (Beatles, 1969), and even backs Lennon in his battle to avoid being expelled from the United States in the 1970s. Incidentally, the Beatles, asked Naked Lunch author, William S. Burroughs, to join them along with Dylan and other big names to pose for the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, forever immortalizing that historic moment.

The nexus of Dylan and the Beat Generation goes back to the first readings of On the Road and ensued with the succeeding fierce complicity with Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti. The bard from the Land of 10,000 Lakes visited Kerouac’s grave with the author of “Howl” during the Rolling Thunder Review tour in November of 1975. Ginsberg opened a book of poems, Mexico City Blues, and read several passages, creating a display of solemn veneration. That was when Dylan decided that he wanted to be buried in an unmarked grave.

After their first encounter, Ginsberg, Kerouac and Cassady become inseparable. In 1992, the poet who spent countless hours with Dylan, said that his own writing had been modeled by Kerouac in terms of a more direct rendering of thoughts and sounds. When asked for his opinion on “Howl”, the novelist advised Ginsberg not to rewrite his first rough draft. Interestingly, the well-known quote “First thought, best thought” was actually advice that Ginsberg took from Jack.

Greil Marcus pointed out in his book Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, that songs like “Visions of Johanna” or “Desolation Road” can be classified as having a very Kerouac-inspired narrative style. Another relevant critic, Clinton Heylin, has stated that the structure of many verses in “Freewheelin’” comes more from Kerouac or Ginsberg than from Guthrie or Robert Johnson.

Allen Ginsberg made an even more striking impact on Dylan. The author of “Howl” was blown away when he first heard “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” in 1963. “Enlightenment has passed from one generation to another. This is the first cultural revolution that has taken place without bloodshed,” pronounced the poet. The two get on like a house on fire and the restless bearded man was even asked to appear in what is sometimes considered to be the first music video in rock history for “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965), behind the Savoy Hotel in London. Marianne Faithfull said that when Dylan throws the signs with the verses of the song written on them on the ground, it’s actually a tribute to On the Road. Chi lo sá.

If we look at the chronology, it’s important to point out that Dylan wrote the tracks for Highway 61 Revisited (1965) only a month and a half after the book Desolation Angels was published, which proved to be the catalyst for not only the title of “Desolation Row”, but also for the feel of the whole album. Dylan talks about name changes (“And give them all another name”), a constant shuffle of names reminiscent of Kerouac and his novels. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (1965) seems to repeat the narrative of the Mexican road trip depicted in On the Road, and “Visions of Johanna” could have perfectly come from the 1963 novel Visions of Gerard.

Much has been written and spoken about Dylan’s motorcycle accident at Woodstock in 1966. Dylanophiles agree that the troubadour was never the same afterwards. However, some still insist that things had already changed for him after reading On the Road, during a time when drifters were in danger of extinction, spurring the musician to cling to their lore. In fact, this led to his declaration of having first rolled into New York on a freight train (although he denied such a thing many years later in his memoirs, confessing that he had actually arrived at the Big Apple by car, another hallmark Beat form of transport).

Over the years, Dylan has distanced himself from those more literary beginnings, but there are still some indications that the initial fire ignited by Kerouac lives on. One piece of evidence can be found in the obvious influence of the Beat writers in Dylan’s first book, Tarantula (released in 1971, even though it was supposed to be published in 1966). Another attestation is The Band’s farewell session in “The Last Waltz”. During that immortal evening, the Minnesotan shared the stage in Frisco with two distinguished poets of the Beat Generation: McClure and Ferliguetti. More proof? The true-to-its-name Never Ending Tour that Dylan kicked off in June of 1988. The name in itself that the Blonde on Blonde composer gave to the Tour is a testimony to his commitment to a life on the road with no expiration date.

Neither Kerouac nor Ginsberg had ever found themselves among the possible candidates for a Nobel Prize for Literature. In 2016, when Dylan received the honors, many fans felt that justice was also being served to the Beat Generation writers. Some critics believe that “Like a Rolling Stone” would have never existed without Ginsberg’s Howl, which, in turn, was directly influenced by Kerouac. In some way, this worldwide recognition extends to all of the groundbreaking artists who suffered during the 1950s until they were able to finally make their way into the elitist American literary scene. The Swedish Academy explained that its decision was heavily rooted in the need to somehow recognize the creation of new poetic expressions in the great American song tradition. When Dylan heard that he had won the prize, he joked, “Nobel? Isn’t that the guy who invented dynamite? […] If someone had ever told me that I had the slightest chance of winning the Nobel Prize, I would have thought that I had about the same odds as standing on the moon.”

Dylan entrusted Patti Smith with the lofty honor of traveling to Sweden to collect the Nobel Prize, due in part to her forerunning role as such an innovative figure, after having straddled the collective territory of punk and rock, forever guided by poetry, her musical compass. As Ronna C. Johnson wrote, “Smith’s art is a driving force behind the cultural and literary transitions from Beat (resistance art) to Pop (imitation art) to Punk (rejection art).”

Poetry, an ingrained contempt towards rules, a high degree of individualism and the necessity for artistic innovation are other common points that Smith shares with the Beats. Although she started out with nothing to her name when she got to New York in 1967, she was already making her poetic declaration of principles in 1975 with Horses. Patti Smith’s unity of poetry and punk music is present on other albums, as well: Seventh Heaven (1972), Easter (1978) or Babel (1978), strengthening New York’s avant-garde and punk. It wasn’t so much about a yearning for the long-gone writers, but rather a vindication of the literary past, in order to foster other emerging forms of alternative culture.

Smith has acknowledged that “almost all the friends that I was into [Sam Shepard or Fred “Sonic” Smith] were crazy about Kerouac. I think I got to know Kerouac kind of second-hand through them.” It’s almost as if the presence of the Visions of Cody author is always there. Not only was Patti Smith close to Burroughs and Kerouac, but she also recited poetry with Gregory Corso and even sang at his funeral in 2001, declaring, “Fortunately, Gregory was a bad influence on me.”

Translation by Jessica Jacobsen