J.P. Harris, según sus propias palabras, no toca Americana ni Roots: él toca Country Music con mayúsculas, música tradicional que actualiza con estilo propio. Es muy revelador, por ejemplo, que su página web lleve por nombre Ilovehonkytonk.com.

Nacido seis minutos antes del Día de San Valentín de 1983 en Montgomery; su familia, después de más de seis generaciones en Alabama, se fue de allí buscando trabajo, iniciando así una peregrinación que les llevo a varios lugares de los States. A los 14 años, cuando acaban de llegar a Las Vegas, J.P. decide marcharse de casa e iniciar una vida llena de aventuras que le llevó a vivir una buena temporada en una reserva india y a trabajar en ocupaciones tan diversas como pastor de ovejas, trabajador agrícola, operador de equipo, leñador, luthier, limpiador de fosas sépticas o carpintero.

Después de pasar mucho tiempo en Vermont, empezó a girar de manera casi amateur por todo el país, hasta que finalmente se estableció en Nashville. Allí debutó discográficamente con «I’ll Keep Calling» con el que obtuvo el galardón de Mejor Álbum Country de 2012 en The Nashville Scene y en los Independent Music Awards, además de colocar dos canciones en la banda sonora de “A cualquier precio”, película protagonizada por Dennis Quaid y Zac Efron.

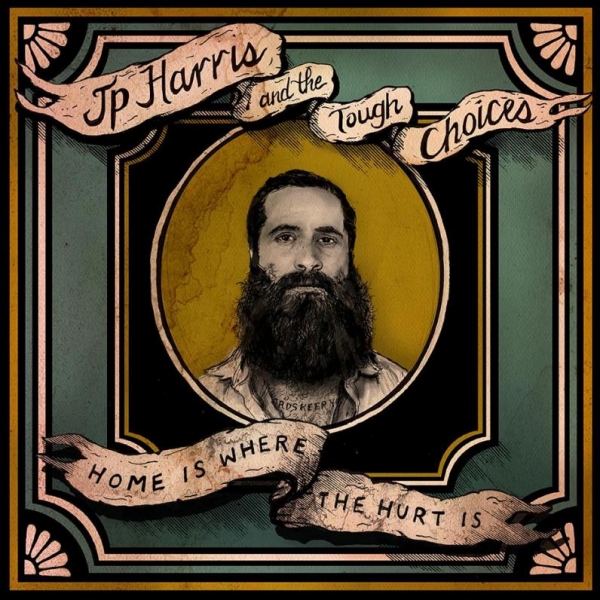

Su último álbum, “Home is where the hurt is” fue grabado en Ronnie’s Place, el mítico studio de Ronnie Milsap y le ha colocado definitivamente entre los artistas más destacados de la escena local, en la que participa activamente. Hace poco ha editado un EP de duetos con varias de las chicas más destacadas de Nashville (Nikki Lane, Leigh Nash, Kelsey Waldon y Kristina Murray)

Su banda, The Tough Choices, es una máquina de honky tonk, como pudimos comprobar en su primera gira española en 2015. Hace unos meses estuvo de nuevo por nuestras tierras junto a Chance McCoy y este verano vuelve a nuestro país, esta vez acompañado por su propia banda, para actuar en el festival country por excelencia: Huercasa. Así que creímos que era un buen momento para tener una charla con él. Una larga conversación en la que nos cuenta detalles de su novelesca vida y nos da muestras de una inquebrantable ética de trabajo. Sin duda, J.P. es un gran tipo, y después de hablar con él nuestra admiración no ha hecho más que crecer.

Creo que hay una gran conexión entre tu música y tu vida. Una vez dijiste «Lo que soy como persona, es lo que soy como músico», así que me gustaría hablar sobre ello.

Siempre he creído que hay una fuerte conexión entre el carácter de un músico y su música. Cuando conozco más sobre la vida personal de un compositor y lo que le llevó a escribir sus textos, tiendo a apreciar más la canción. Aunque no entro en grandes detalles sobre mi vida personal, todas mis canciones son reflejos de ella. No quiero que haya una separación entre el «yo real» y el «yo en el escenario“.

Tu familia se fue moviendo desde Alabama a otros lugares hasta terminar en Las Vegas. ¿Por qué decidiste a la edad de 14 coger un par de camisetas y 42 dólares y saltar a bordo de un Greyhound?

Explicar todas las razones por las que me fui tan joven de casa daría para toda una entrevista… Pero digamos que sabía que no encajaba en la sociedad «normal» en la que vivía y que tenía mucho más por ver y por hacer. Salir de casa a una edad tan temprana me enseñó a cuidar de mí mismo, a confiar y ver la bondad de los extraños, y me obligó a ser mucho más abierto de mente. No me he arrepentido mucho de eso.

Te fuiste a Oakland, California, porque te gustaba su escena punk rock, ¿cuándo empezaste a tocar música country?

Había escuchado a unos cuantos artistas country cuando todavía estaba metido en el mundo del punk rock … Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, The Statler Brothers, … Cuando salí de casa ya no tenía donde conectar una guitarra eléctrica, así que gravité de forma natural hacia la música acústica. Conseguí varias guitarras baratas en casas de empeño cuando todavía viajaba a pie y aprendí que tocar en la calle era una buena manera de conseguir dinero. Las historias que hay en las viejas canciones del country empezaron a resonar conmigo. Conseguí una vieja cinta de Johnny Cash y aprendí todas sus canciones, seguí con Hank Williams, luego ya más profundamente con The Carter Family y las verdaderas old ballads. Con 17 años ya sabía que lo que quería tocar era música tradicional.

Cuéntanos algo sobre tu tiempo como pastor de ovejas con los navajos. Creo que es realmente interesante.

Los Navajo (o Dineh como se conocen tradicionalmente) son la tribu más grande de América del Norte. Como sucede con la mayoría de las tribus nativas americanas, han sido reubicados a la fuerza, trasladados de parcela a parcela, y recientemente sus tierras han sido expropiadas para la extracción de minerales. Me había cansado de la ciudad y me involucré en las campañas de Derechos de los Nativos … Sentí a la vez la necesidad de escapar del ambiente urbano en el que crecí y las ganas de lograr un cambio en algún lugar, así que me subí a un autobús escolar conducido por una vieja pareja hippie y me fui a Arizona.

Es una historia larga, con muchos matices diferentes, pero la versión corta es que el suroeste de los Estados Unidos se ha vuelto dependiente de la energía producida en las minas masivas de carbón y de uranio que hay en la reserva de los Navajos. A través de una serie de políticas retorcidas del gobierno, se decidió que había un «conflicto territorial» entre las tribus Hopi y Navajo; La «zona en disputa» resultó estar en la cima del filón de carbón más grande del oeste, y la Oficina de Asuntos Indígenas ha estado tratando durante décadas de echar a estas personas de su tierra. Muchos de sus hijos fueron enviados a escuelas indias fuera de la reserva, o abandonados en las ciudades para que buscaran trabajo, dejando a los ancianos navajos solos para sacar adelante su pastoreo y sus cultivos.

No sólo aprendí mucho acerca de vivir en el hostil clima del desierto, sino también pastoreo, construcción tradicional y, lo que es más importante, una comprensión de la espiritualidad nativa: la conexión con la tierra en todos los sentidos y la apreciación de sus dones incluso en tierra estéril. Estas cosas permanecerán en mi para siempre. También aprendí mucho acerca del respeto a los ancianos; aumentó mucho mi comprensión del impacto del colonialismo blanco sobre los pueblos indígenas de este continente y entendí más sobre mi propio papel en cómo continúa aquí hoy en día.

Muchos jóvenes viajan a través el país por razones románticas, al estilo Woody Guthrie. ¿También fue algo romántico para ti? ¿Usas esa parte de tu vida como inspiración?

Jaja … ¡POR SUPUESTO que fue romántico! Los años que viajé constantemente, éstos fueron mis primeros sorbos de libertad, la anarquía, mi propio poder para de alguna manera decidir mi propio destino… Nunca olvidaré ese sentimiento. La primera vez que salté un tren de mercancías estaba aterrado pero me sentía más vivo que nunca. Supongo que llevar esa forma de vida desde el principio es la razón por la que nunca he tenido un trabajo «normal» y nunca he trabajado realmente para otra persona. Simplemente decidí que, para bien o para mal, nadie me diría cómo vivir mi vida.

También conocí a muchas personas diferentes. Yo era un chico punk joven, enfadado, idealista y muy crítico con el mundo «normal» que me rodeaba. A menudo esto me hizo pasar por alto la genuina bondad o las buenas intenciones de muchas personas, pero viajar me mostró que en cada persona hay mucho más que sus antecedentes, su ropa o incluso a quien dé su voto. Los trabajadores del ferrocarril me dieron propinas, botellas de agua, incluso comida; alguien me recogía haciendo autostop, me compraba el almuerzo y conducía más allá de su destino solo por ayudarme. En todos mis años predicando tolerancia había pasado de mucha gente y la carretera me enseñó a dar una oportunidad a todo el mundo, a confiar en la buena naturaleza de las personas hasta que se demuestre lo contrario.

Luego pasaste una década de tu vida en Vermont, sobreviviendo con trabajos duros. ¿Alguna vez pensaste en abandonar tu sueño de ser músico?

Vermont fue, en muchos sentidos, el estado en el que crecí de verdad. Me sentía un poco fuera de lugar: tras crecer en torno a una familia sureña me vi de repente en una cultura rural muy diferente, pero la gente allí trata a los demás con muchísimo respeto… la actitud es «no me molestas, no te molestaré «, y siempre te paras a ayudar a sacar el coche de un desconocido de una zanja o a apartar un árbol caído junto a un vecino. ¡Allí es muy doloroso no contar con la amabilidad de los desconocidos!

Siempre me encantó la música, pero nunca pensé que la perseguiría profesionalmente. Creo que me convertí en un hombre viejo rápidamente. Cuando tenía 23 o 24 años ya poseía un pedazo de tierra, dos camiones, un bulldozer y un granero lleno de equipamiento y herramientas. Pienso que podría haber llegado a ser un colono de esos que apenas hacen vida fuera del bosque en el que talan la madera y que siempre acarrea su agua, pero simplemente hay algo que no me deja estar demasiado tiempo lejos de la carretera. Nunca quise ser un músico «real», simplemente es algo que pasó.

Ahora vives en Nashville. Siempre hablas muy bien de la comunidad musical de la ciudad. ¿Te adaptaste fácilmente a la ciudad?

Nashville es una gran ciudad, y la ha hecho grande sobre todo la gente que vive aquí. Todavía me enfado cuando por las mañanas no puedo caminar desnudo por mi jardín con una taza de café, pero por ahora estoy feliz aquí. Sé que algún día estaré enfermo de nuevo y regresaré a los bosques, pero creo que siempre estaré cerca de Nashville.

Eres el carpintero oficial de esa comunidad musical. Creo que es interesante que sigas trabajando fuera de la música, porque sigues en el lado de los trabajadores. ¿Qué piensas sobre esto?

Sí, supongo que podríamos decir que me he convertido oficialmente en el «carpintero de las estrellas». Nunca me he identificado a mi mismo como músico, sino más bien como un trabajador, y ponerme un cinturón de herramientas cuando no estoy de gira me mantiene conectado con mi identidad trabajadora. Sin duda eso ha dado forma a mi estética musical y sentir que tengo algo más que ofrecer al mundo me mantiene cuerdo. Además, ¡cobrar por horas no está nada mal!

No tienes ni un minuto de descanso: tus propios discos, duetos, tours con tu banda, tours con Chance McCoy, … ¿es algo planeado o vas improvisando según las circunstancias?

No, no hay descanso para los cansados. Probablemente he tenido unas 10.000 horas de sueño en el transcurso de mi vida, pero tendré mucho más cuando muera. No me gusta el tiempo de ocio, no me gusta sentarme en la playa sin nada que hacer, tengo que estar ocupado. Es como si me hubiese retado a mi mismo para ver cuánto trabajo puedo abarcar, y aun así suelo quedar por delante de mis expectativas. Pero también estoy muy desilusionado por la actitud de vagancia que tienen algunos músicos, quejándose de estar destrozados cuando no están de gira pero que no están dispuestos a coger una pala y cavar una maldita zanja. Soy un cantante country y eso lleva consigo una actitud country: el día en que dejas de trabajar es el día en que empiezas a morir. Retirarse es algo de mamones.

Nos encantan The Tough Choices. ¿Fue fácil reunir a una banda tan buena?

Siempre he sido muy afortunado por tener tan grandes músicos en mi banda. Las caras cambian, me abandonan por otros proyectos y vuelven después de unos años… puede ser a veces frustrante tener una banda con mucha rotación, pero también me ha hecho un mejor líder, un mejor músico y una persona más tolerante y comprensiva. Nashville es una enorme cantera de grandes instrumentistas hambrientos por trabajar, y estoy muy agradecido de que a pesar de que haya habido épocas malas, mucha gente ha estado a mi lado a lo largo de los años.

Creo que el éxito de Sturgill Simpson o Margo Price ha sido una buena noticia para los que no disfrutamos del mainstream country. Artistas que respetan la tradición pero suenan frescos y contemporáneos, ¿qué piensas de ellos?

Realmente estoy orgulloso de ambos artistas, y estoy de acuerdo en que su éxito es bueno para todos nosotros. Es realmente agradable ver genuinos músicos country que hacen lo que quieren sin compromisos, aunque su sonido sea diferente del mío. Hay un montón de fans del viejo country por ahí que odian lo que está sonando en la radio, pero no saben cómo encontrar a gente como yo, y en estos tiempos cada vez es más fácil gracias al boom de ese country más tradicional.

Tocarás en Huercasa con Shooter Jennings y Aaron Watson. Son dos visiones diferentes de la música country. ¿Cual prefieres?

Bueno, no puedo elegir un favorito, ¡los dos son grandes en lo que hacen!

¿Cuáles son tus planes a corto plazo? ¿Continuar de gira? ¿Un nuevo disco?

Este año tengo tours con mi propia banda, uno con Chance McCoy, y otro mes en el norte de Europa y Escandinavia. Aún no lo he anunciado oficialmente, pero finalmente voy a meterme en el estudio para hacer un nuevo disco, de hecho apenas dos días después de que volvamos de Huercasa. No puedo hablar mucho de ello, pero estoy muy entusiasmado con los músicos, el estudio, el ingeniero y el productor con el que estoy trabajando. Con un poco de suerte saldrá a principios de 2018, y puedo decir que estoy muy orgulloso de las nuevas canciones también…

I think there’s a great connection between your music and your life. Once you said “That’s who I am as a person, it’s who I am as a musician”, so talk about this.

I have always believed there is a strong connection between a musician’s character and their music. When I know more about a songwriter’s personal life, what led them to the words they write, I tend to appreciate the song more. Although I don’t go into great detail about my personal life, all of my songs are reflections of it. I don’t want there to be a separation of the «real me» and the «stage me.»

Your family move from Alabama to other places and finished in Las Vegas. Why you decide at the age of 14 to split and I stuck a couple of T-shirts and $42 and jumped on a Greyhound?

To explain all of the reasons I left home so young would take a whole other interview…but let’s just say I knew I didn’t fit in the «normal» society I was living in, and had a lot more to see and do. Leaving home at a young age taught me to take care of myself, to rely on and see the kindness of strangers, and forced me to be much more open-minded. I don’t regret much of it.

You went to Oakland, California, because you liked the punk rock scene, when did you begin to play country music?

I had listened to a few country artists when I was still deep into the punk rock world…Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, The Statler Brothers…when I left home I no longer had anywhere to plug in an electric guitar, so I naturally gravitated towards acoustic music. I had several cheap old pawnshop guitars when I was still traveling on foot, and learned that performing on the street was a good way to make money. The stories in the old country songs started to resonate with me; I got an old Johnny Cash tape and learned all the songs on it, then on to Hank Williams, then deeper into The Carter Family and the really old ballads. By the time I was 17 I knew that traditional music was what i wanted to play.

Tell us something about your time as a sheep herder with the Navajo. I think it´s really interesting.

The Navajo (or Dineh as they are traditionally known) are the largest tribe in North America; similar to most all Native American tribes, they have been forcibly relocated, moved from parcel to parcel, and most recently had their lands seized for mining or mineral extraction. I had grown sick of the city, and become more involved in Native Rights campaigns…I felt like I wanted to both escape the urban environment I grew up in and make a difference somewhere, so I jumped on a school bus driven by an old hippie couple and went to Arizona.

It is a long story, with many different sides, but the short version is that the southwest United States has become reliant on massive coal and uranium mines on the Navajo reservation for energy. Through a series of crooked government policies, it was decided that there was a «land conflict» between the Hopi and Navajo tribes; the «disputed area» just so happens to be on top of the largest coal deposit in the west, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs has been trying to remove these people from this land for decades. Many of their children were sent to off-reservation Indian Schools, or left seeking work in the cities, leaving many elderly Navajo to carry on their sheepherding and farming alone.

I learned not only much about living in the hostile desert climate, but sheepherding, traditional building, and most importantly an understanding of Native spirituality; the connection to the earth in every way, the appreciation of its gifts even in the barren sand,… These things will stay with me forever. I also learned a lot about respecting the elders; I realized much more of the impact of white colonialism on the indigenous people of this continent, and understood more of my own role in how it continues here today.

Young people travels through the country for romantic reasons, like Woody Guthrie. Did it ever feel like something romantic to you? Do you use that part of your life as inspiration?

Haha…of COURSE it was romantic! The years I traveled constantly, those were my first tastes of freedom, lawlessness, my own power to in some way decide my own fate…I will never forget the feeling of it. The first time I jumped a freight train I was terrified and felt more alive than ever before. I guess that way of life early on is why I’ve never held a «straight» job or really worked for anyone else. I just decided that for better or worse, no one would tell me how to live my life.

I also met so many different people. I was a young, angry, idealistic punk kid, and was very judgmental of the «normal» world around me. Often this made me overlook the genuine kindness or good intentions of many people, but traveling showed me that there is much more to a person than their background, their clothes, or even who they vote for. Railroad workers would give me tips or bottles of water, even food; someone would pick me up hitchhiking and buy me lunch or drive me well-past where they were going just to help me out. In all my years of preaching tolerance I had overlooked a lot of people, and the road taught me to give everyone a chance, to believe in the good nature of people until proven wrong.

Then you spent a decade of your life in Vermont, surviving with dirty jobs. Did you ever think of quitting your dream of being a musician?

Vermont was, in many ways, the state that truly raised me. I felt somewhat out of place, growing up around a southern family and suddenly living in a very different rural culture, but people up there treat each other with a great deal of respect…the attitude is «you don’t bother me, I won’t bother you,» and you always stop to pull a stranger’s car out of the ditch, or move a fallen tree with a neighbor. It’s too damn cold up there not to count on the kindness of strangers!

I always loved music but never thought I’d pursue it professionally. I guess I grew into an old man fast, and by the time I was 23 or 24 owned a piece of land, two trucks, a bulldozer, and a barn full of equipment and tools. I thought I’d be a homesteader of sorts, just live out in the forest chopping wood and carrying my water forever, but something just wouldn’t let me stay away from the road any longer. I never intended to be a «real» musician, it just sort of happened that way.

Now you live in Nashville. You always talk very well about the city’s musical community. Did you adapt easily to the city?

Nashville is a great city, made great mostly by the people that live here. I still get mad when I can’t walk out in my yard naked with a cup of coffee every morning, but for now I’m happy here. I know that sometime soon I’ll be sick of it again, and head back to the woods, but I think I’ll always stay close to Nashville.

You are the official carpenter on this music community. I think it’s interesting that you keep working out of music, because it places you on the side of working people. What do you think about this?

Yes, I guess I have become the official «carpenter to the stars» as we say! I have never truly identified myself as a musician, but more as a working person, and putting on a tool belt when I’m not on tour keeps me connected to my working identity. It has most certainly shaped my musical aesthetic, and keeps me sane by feeling that there is something else I have to offer the world. Also getting paid by the hour ain’t bad!

You do not have time to rest: your own records, duets, tours with the band, tours with Chance McCoy,… is it something planned or improvised depending on the circumstances?

Nope, no rest for the weary. I’m probably about 10,000 hours behind on sleep over the course of my life, but I’ll have plenty when I’m dead. I don’t like idle time, I don’t like sitting at the beach with nothing to do, I just have to stay busy. It’s almost like I’ve dared myself to see how much work I can handle, and I just barely stay ahead of it. But I also am very turned off by the slacker attitude many musicians have; complaining about being broke when they’re not on tour but being unwilling to pick up a shovel and dig a damned ditch. I’m a country singer, and that comes from a country attitude: the day you stop working is the day you start dying. Retirement is for suckers.

We love The Tough Choices. Was it easy to put together such a good band?

I have always been very fortunate to have such great players in my band; the faces change, they leave for other projects and come back over the years…it can be frustrating at times to have a rotating band, but it’s also made me a better band leader, a better musician, and a more tolerant and understanding person. Nashville is such a wealth of great players who are hungry for work, and I am just so appreciative of the hard times so many people have put in with me over all the years.

I think the success of Sturgill Simpson or Margo Price is good news for those of us who do not enjoy the mainstream country. Artists who respect tradition but sound fresh and contemporary, what do you think of it?

I’m proud of both those artists for sure, and agree that their success is good for us all. It’s really nice to see genuine country musicians doing what they want without having to compromise, even if their sound is different than mine. There are a lot of regular old country fans out there who hate what’s on the radio but don’t know how to find folks like me, and these days it’s getting easier thanks to the boom in more traditional country.

You play in Huercasa with Shooter Jennings and Aaron Watson. They are two different visions of country music. Which do you prefer?

Well, I can’t play favorites but they’re both great at what they do!

What are your short term plans? Continue on tour? A new record?

I have tours this year with my own band, a duet tour with Chance McCoy, and another month in northern Europe and Scandinavia; I haven’t officially announced it yet, but I’m finally going into the studio to make a new record, in fact just two days after we return from Huercasa. I can’t talk much about it, but I’m very excited about the players, studio, engineer, and producer working on it. With any luck it will be out early 2018, and I can say that I’m very proud of the new songs as well…